On Wednesday, November 27th, the MTI office will close early at 1 PM ET for the Thanksgiving holiday weekend. Office operations will resume on Monday, December 2nd.

Filichia Features: Learning from Lerner

Filichia Features: Learning from Lerner

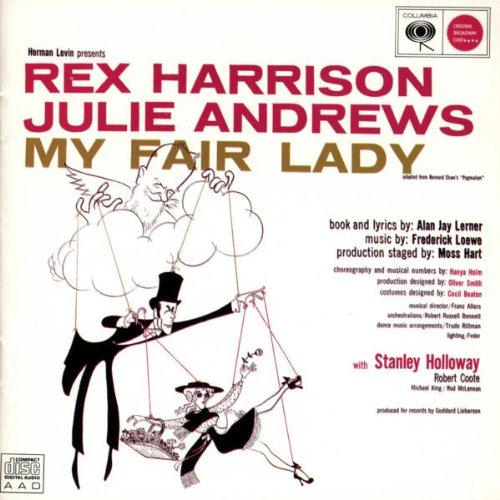

As entertaining as Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe’s My Fair Lady and Camelot are, they also teach valuable lessons.

My Fair Lady suggests that an underprivileged woman has more to her than meets the eye. Give her the right opportunities and she’ll take her place with the best of society.

Camelot stresses that altruism and lofty goals may not always succeed but they shouldn’t be abandoned. They must be tried again.

While Lerner was creating these musicals, he learned a few lessons himself. They’re ones we should remember, too.

Don’t Be Insulted If You’re Not the First Choice

Wasn’t Lerner wonderfully flattered when Gabriel Pascal, the esteemed producer of the 1938 film Pygmalion, asked him to musicalize George Bernard Shaw’s play?

Well, yes and no. As Lerner explained in his memoir The Street Where I Live, “We never mentioned to him that we knew he’d offered it to Rodgers and Hammerstein.”

If at First You Don’t Succeed …

R&H had actually taken Pascal’s offer and had started writing. Lerner recalled that some time later, he ran into Oscar Hammerstein who told him in no uncertain terms “It can’t be done. We tried for a year.”

Well, when a Hammerstein talks, you listen. So in 1952, Lerner and Loewe stopped musicalizing Pygmalion.

Needless to say, they – and we – are very glad that they returned to it.

Be Willing to Change

Even then, things didn’t go swimmingly. Many a musical theater enthusiast knows that Rex Harrison said “I hate them” after he heard two songs for Higgins. A more famous story has Mary Martin listening to four that made her claim “those dear boys have lost their talent.”

What isn’t often said is that some of those songs didn’t wind up in the My Fair Lady we know and love. As Lerner admitted, “The first attempts are frequently stopovers on the way to the eventual destination.”

Perhaps if Martin heard what eventually wound up in the show, she would have changed her mind – as Harrison did.

Do Every Kind of Research Possible

After Lerner told two-time Oscar-winning director Lewis Milestone that he was musicalizing Pygmalion, Milestone asked if he’d been to Covent Garden, where the first scene of Shaw’s play occurs. Lerner said no, which made Milestone insist they meet there – at four in the morning, the precise time that Eliza would be there selling flowers.

Lerner, despite his notoriously slowness in creating lyrics, had enough inspiration to finish “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” three days later.

The More You Work, The Easier It Gets

Writing a musical is not unlike working on a jigsaw puzzle.

You first find the pieces with the edges. So far, there’s not much difficulty, for making up the puzzle’s border isn’t difficult -- just as penning an outline for a musical is easier than writing the entire show.

However, filling in the rest of the pieces is much harder -- as is writing the right songs and scenes. And yet, the more pieces you place into the puzzle, the faster you’ll insert the remaining ones.

Similarly, the more you write, the quicker you’ll find the show coming together. So while Lerner reports that he spent weeks and even months on many songs, by the time he got to “I Could Have Danced All Night” and “The Rain in Spain” late in the game, the former took only a day’s work and the latter, he claims, took ten minutes.

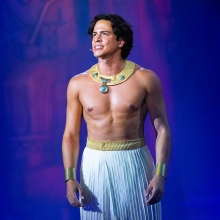

Julie Andrews, Rex Harrison and Robert Coote in My Fair Lady.

Julie Andrews, Rex Harrison and Robert Coote in My Fair Lady.

Listen Carefully to Everyone around You

Lajos Egri, author of The Art of Dramatic Writing, pointed out that “A good writer is a good stenographer.” He wasn’t suggesting that writers learn shorthand, but meant that they should listen carefully to real-life people and write it, if not verbatim, then close to it.

Lerner admits that a chance remark that Harrison made while walking provided the inspiration for “A Hymn to Him” – better known as “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man?”

Thank you, Rex!

It’s Not Where You Start – It’s Where You Finish

Mid-January, 1956, the My Fair Lady staff started to believe that Julie Andrews wouldn’t be able to do justice to Eliza Doolittle. There was serious talk of replacing her.

In mid-March, a mere two months later, Andrews was hailed by all the New York critics for her radiant performance that cemented her brilliant career. So don’t automatically give up on that performer who just isn’t getting it. Take him or her aside, as director Moss Hart did with Andrews, and get what you and the performer need.

Defuse Controversies with Humor

During rehearsals, Harrison often felt that Shaw’s spirit was being violated. He wanted to prove his point by referencing the original play. “Where’s my Penguin?” he’d ask, meaning the paperback that had been published by that company.

Lerner soon wearied of this, so he had a stuffed penguin made and stored backstage. The next time Harrison roared “Where’s my Penguin?” Lerner had the taxidermed sphenisciforme spheiscidae brought out, which gave Harrison a good laugh – and stopped him from demanding the book.

Temperament Often Means Something Else

The dictionary defines “temperament” as “a person's or animal's nature, especially as it permanently affects their behavior.” Lerner wrote that Harrison exhibited a great amount of it just before My Fair Lady’s first out-of-town performance. What brought it on? Lerner has the explanation: “Temperament is based on one thing only: fear.”

So when your actors start acting up, calm them so they can start acting.

There Are No Small Parts …

When Roddy McDowall heard that Lerner and Loewe were writing Camelot, he begged to play Mordred, Arthur’s illegitimate ne’er-do-well son. Lerner made clear that the part was small – so small that Mordred doesn’t even make an appearance until the second act. McDowall insisted, so director Moss Hart acquiesced. Said Lerner, “And by skill and sheer personality, he made it a star part.”

Teach that lesson to your Mordred -- and to your Mrs. Higgins in My Fair Lady, too.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com and Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com. His book, The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.