On Wednesday, November 27th, the MTI office will close early at 1 PM ET for the Thanksgiving holiday weekend. Office operations will resume on Monday, December 2nd.

Filichia Features: The Story of The Story of My Life

Filichia Features: The Story of The Story of My Life

You may know the song entitled “The Story of My Life” from Shrek, but do you know the musical called The Story of My Life?

It has nothing to do with Pinocchio, Peter Pan or Papa Bear, as Jeanine Tesori and David Lindsay-Abaire’s song does. Instead, it’s a tale of a boymance that never advanced to a bromance.

Know the terms? A bromance, according to the now-accepted definition, is a close non-sexual relationship between two men.

Would that Thomas Weaver and Alvin Kelby had had that. What they did have during their grammar school years in upstate rural New York was what we might call a boymance: a close non-sexual relationship between two boys.

In Neil Bartram and Brian Hill’s excellent two-character musical, Thomas and Alvin meet in first grade and are encouraged into friendship by their teacher Mrs. Remington. “She knew,” sings Thomas, “that the battlefield of childhood was easier with two.”

Alvin is the more fanciful of the two. Most lads, especially in a bygone era, would take out knives and heroically slice their fingers in order to become blood brothers. Alvin instead would rather discuss how each would eulogize the other at his funeral when that day came.

After school one day, when Alvin tells Thomas that he’s bringing him to “a mystical place,” the more mundane Thomas is a little surprised to find, “It’s a bookstore.” Yes, Alvin’s daddy runs a used bookstore, where he prides himself on being able to pick out the perfect book for each customer. Alvin believes he has that ability, too, and he turns out to be right when he gives Thomas a novel that greatly moves him: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Thomas’ book report reveals that he has the mind, style and originality of a great writer when he mentions that the book was written in 1876 – which made it “so much better than 1875.”

And so, the two have, to reference the title of a song from A Class Act, “The next best thing to love.” But any fast friendship can spring a slow leak, and it happens here. As both reach high school age, Thomas becomes more conventional in nature while Alvin continues to be eccentric. After they’re graduated, Thomas is glad to be going away to college and away from Alvin, who neither leaves town nor advances past high school. The once inseparable friends are now officially separated.

Thomas becomes a best-selling author; Alvin takes over his father’s bookstore. Yes, Thomas comes back home when Alvin’s father dies, but we know that all is not well between the two when Alvin’s first words to his pal are “You’re late.” Matters devolve when Alvin hears the eulogy that Thomas wrote – nay, copied, for he pretty much quoted a John Donne poem and left it at that. Alvin is devastated that this acclaimed writer suddenly couldn’t find the words, and knows he simply didn’t care enough to try.

Worse is to come. Thomas invites Alvin to the Big City, the prospect of which excites the stay-at-home to no end. But then, at the last minute, Thomas says, “Alvin, don’t come.”

How well I remember the gasp of horror from the audience at the Booth Theatre on Feb. 22, 2009. That was proof positive to me that The Story of My Life had fully engrossed its audience. What’s often said is that “musicals are about big characters and big events,” and we’ll all admit that a Phantom’s causing a chandelier to fall proves the point. But for an audience to be so moved by a retracted invitation shows how much they cared about Thomas and Alvin.

The critics didn’t, and The Story of My Life called it a life after that first weekend. That day, co-producer Jack M. Dalgleish told me that he and his partners decided to spend the money left in the budget to record a cast album; that way, others would hear the work and be inspired to mount a future production – such as the one we’re currently getting at the Delaware Theatre Company in Wilmington.

Funny; when I heard that Rob McClure and Ben Dibble had been cast, I didn’t know which role each would play. I’d been cheering on McClure since his college years at Montclair State University and wasn’t surprised when he got raves (and a Tony nomination) for playing the title role in Chaplin. And while I only caught up with Dibble since he became a star at the Arden Theatre Company in Philadelphia (and most recently lauded him for his Leo Frank in Parade), I certainly have been equally impressed with him. Each actor was so versatile, then, that I could picture either as Thomas or Alvin.

Director Bud Martin, who co-produced the Broadway production, saw Dibble as Thomas and McClure as Alvin, and both did him proud. As in the original, no attempt was made for these grown men to adopt children’s voices when they played their younger selves. I doubt that anyone missed the cherubic sounds of childhood or the squeaky voices of adolescence.

After the “Alvin, don’t come” phone call, McClure conveyed that his “Goodbye” was a final one. That’s the one consolation of being a loyal friend; he doesn’t have to feel guilty, because he’s always made himself available to his pal. When McClure sang the song called “You’re Amazing, Tom,” in which he ostensibly praised “the money and the prizes,” he was able to get across the fascinating subtext: Tom amazed him in how insensitive he can be without realizing it. McClure was even able to do an excellent Jimmy Stewart imitation (which isn’t a necessity, but a lagniappe; a good deal of the story references the actor’s 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life).

Dibble was poignantly effective in feeling a different type of survivor’s guilt. When he said “We gradually lost touch,” his face betrayed that he knew he was using a euphemism. Dibble also made us see that Thomas was a workaholic, but that such discipline might be necessary to reach the goal of being a successful writer.

ore to the point, Dibble displayed Thomas’ need to think that he became successful all by himself. But no one does. The Story of My Life has more than one valuable lesson to teach. Many budding actors already believe that they’re the sun, moon and a future sure-fire successes that they decline help from their betters; once they make it, they don’t want to be indebted to anyone. But making it is substantially harder without mentors or at the very least, people to inspire you – as Alvin inspired Thomas by being the writer’s first appraiser (a term I prefer to critic) and giving him validation when he needed it in his formative years.

Here, Dirk Durosette’s set greatly resembled the one seen on Broadway. Virtually everything was white: the podium where Thomas lectured; the library ladder on wheels that provided the two characters with a place to sits; eight white mini-bookcases with books with white dust jackets. White papers were scattered in a geometric pattern over one flat stage right. Even the three-page Playboy centerfold that Thomas appreciated (and Alvin didn’t) was solid white.

That’s what you’ll need – not to mention close to a ream of white paper for every performance. Thomas often starts to write on a piece and then crumples it and throws it on the floor. During a flashback, those wadded-up pieces later serve as snowballs, as shredded bits fall from above to replicate a snowfall.

It’s a nice show that advocates a love of learning, as well as an appreciation for individuality. That does bring us back to Shrek, doesn’t it, which suggests “Let Your Freak Flag Fly”? Did Alvin “never grow up” or was he able to do what Thomas didn’t dare: maintain his zest, curiosity and native joy? Who says that there must be a statute of limitations in having a childlike enthusiasm of life?

But The Story of My Life offers substantially more. When Fields of Dreams debuted in 1989, many articles about the film mentioned how men were leaving the theater in tears. It’ll happen, too, with The Story of My Life, a musical for anyone who’s had, lost or dropped a friend – or, more’s the pity – done the dropping. How interesting that we live in an age where we don’t raze old buildings because we consider them National Historic Landmarks – and yet we don’t give nearly as much thought to old friendships and routinely tear them down. They should be considered our own personal National Historic Landmarks.

So consider staging The Story of My Life at your theater – and not simply because your two actors will be off book faster because so much of the show has them reading from pages that are right in front of them. It’s an ideal show for brothers, good friends or even now-estranged but one-time good friends. After doing it, they may not be estranged any longer.

Indeed, many audience members who see it will be motivated to get on the phone or the Internet, find their ol’ pals and rekindle what they used to have. If a musical can do that, it’s really something special. So just as Alvin insists on finding for Thomas “the book you never knew you needed,” The Story of My Life may well be the musical you never knew you needed.

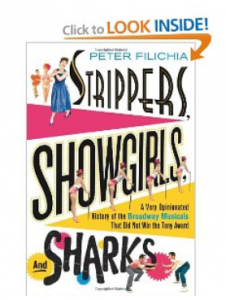

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.